KING BILLY

The following piece was written by Bert Spinks and was published as "The Man Who Died on Goulburn Street"

People like to tell the story of what happened to William Lanne after he died. He was, they say, only 34 years old when he passed away from cholera. With his body in the hospital morgue, the chief medical scientists of the day came and hacked off his body parts. Buried the next day, he was dug up again and dismembered further.

He was, after all, a significant scientific novelty: William was the last captured Aboriginal man left on the island.

In his early days, he was moved around like a pinball. Born in the north-west of Van Diemen's Land, he was first removed with his family to Flinders Island in 1842, when he was seven; then, his parents having died like so many other Aborigines at the Wybalenna camp, they sent William to Bruny Island. After that, he was enrolled at the orphan school in Hobart.

He left the school at 16. Rootless, without a family, his race disintegrating around him, William got himself a job on a ship. He sailed out onto the Pacific Ocean as a 'whale spotter'. They say he had the best eyes on the whole ocean; if anyone could spot a whale, it was William Lanne. He spent a lot of long days looking on that water, out to the horizon.

He came back to Hobart and lodged at The Dog & Partridge on Goulburn Street. By that point, the island was no longer called Van Diemen's Land; it had a new name, a more euphonious one (if that's possible), one that wasn't so inextricably linked to acts of grisly violence, like those that happened in the early days of the colony.

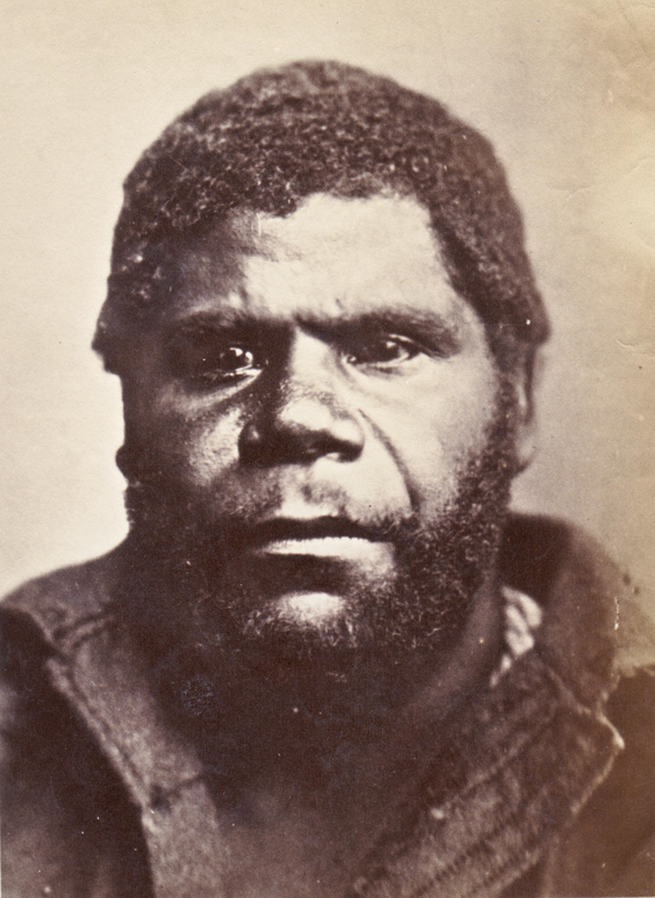

Sickness had a grip on him already. He coughed and spluttered, but did not give up smoking his pipe. A burly man, dressed now in heavy jackets and ragged pants, William had the face of a rugby player, but the eyes of a marsupial. His shipmates, and the Hobart locals, called him King Billy. It is not recorded how he responded. From the photographs of him, you might guess he took it gently, stoically.

Nowadays The Dog & Partridge has been turned into some kind of backpackers' hostel. The Church of Christ up the road still stands in all its sandstone glory, but it's become a private residence. There's an art gallery, a laundromat, and the Pigeon Hole cafe has good coffee. That's what it's like now: a tumult of change, jarring and jolting shifts that you either have to adapt to or be abandoned by.

Sometimes life just gets pulled out from under you.

PREVIOUS // NEXT

People like to tell the story of what happened to William Lanne after he died. He was, they say, only 34 years old when he passed away from cholera. With his body in the hospital morgue, the chief medical scientists of the day came and hacked off his body parts. Buried the next day, he was dug up again and dismembered further.

He was, after all, a significant scientific novelty: William was the last captured Aboriginal man left on the island.

In his early days, he was moved around like a pinball. Born in the north-west of Van Diemen's Land, he was first removed with his family to Flinders Island in 1842, when he was seven; then, his parents having died like so many other Aborigines at the Wybalenna camp, they sent William to Bruny Island. After that, he was enrolled at the orphan school in Hobart.

He left the school at 16. Rootless, without a family, his race disintegrating around him, William got himself a job on a ship. He sailed out onto the Pacific Ocean as a 'whale spotter'. They say he had the best eyes on the whole ocean; if anyone could spot a whale, it was William Lanne. He spent a lot of long days looking on that water, out to the horizon.

He came back to Hobart and lodged at The Dog & Partridge on Goulburn Street. By that point, the island was no longer called Van Diemen's Land; it had a new name, a more euphonious one (if that's possible), one that wasn't so inextricably linked to acts of grisly violence, like those that happened in the early days of the colony.

Sickness had a grip on him already. He coughed and spluttered, but did not give up smoking his pipe. A burly man, dressed now in heavy jackets and ragged pants, William had the face of a rugby player, but the eyes of a marsupial. His shipmates, and the Hobart locals, called him King Billy. It is not recorded how he responded. From the photographs of him, you might guess he took it gently, stoically.

Nowadays The Dog & Partridge has been turned into some kind of backpackers' hostel. The Church of Christ up the road still stands in all its sandstone glory, but it's become a private residence. There's an art gallery, a laundromat, and the Pigeon Hole cafe has good coffee. That's what it's like now: a tumult of change, jarring and jolting shifts that you either have to adapt to or be abandoned by.

Sometimes life just gets pulled out from under you.

PREVIOUS // NEXT