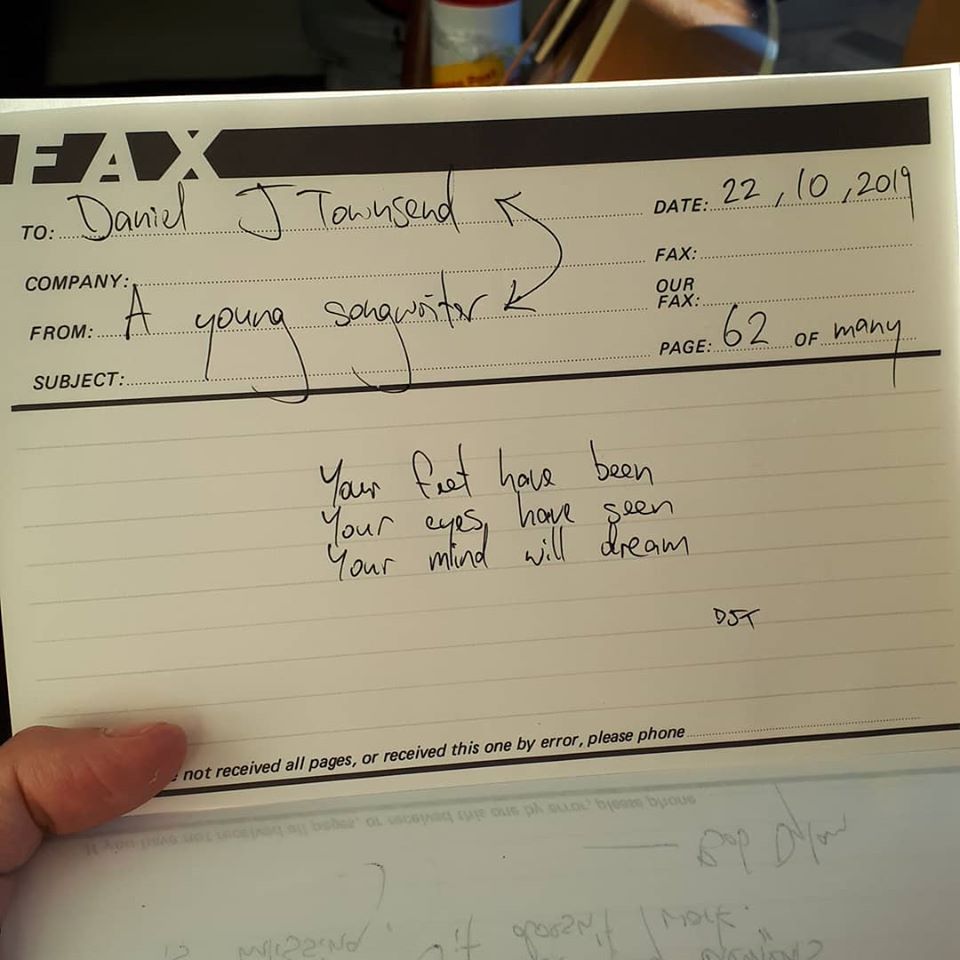

When Bob Dylan moved to New York City, he did so with the intention of solely singing other people's songs. Old songs. In other words, he wanted to be a folk singer.

He had learned hundreds of songs from a bunch of sources. Rare records, late night radio, that singer in the music store. Each song had a story or three, most had multiple versions from multiple performers, some had more than a dozen verses. Thousands of words. Memorised the lot of them and knew them deeply. Like I said, a folk singer.

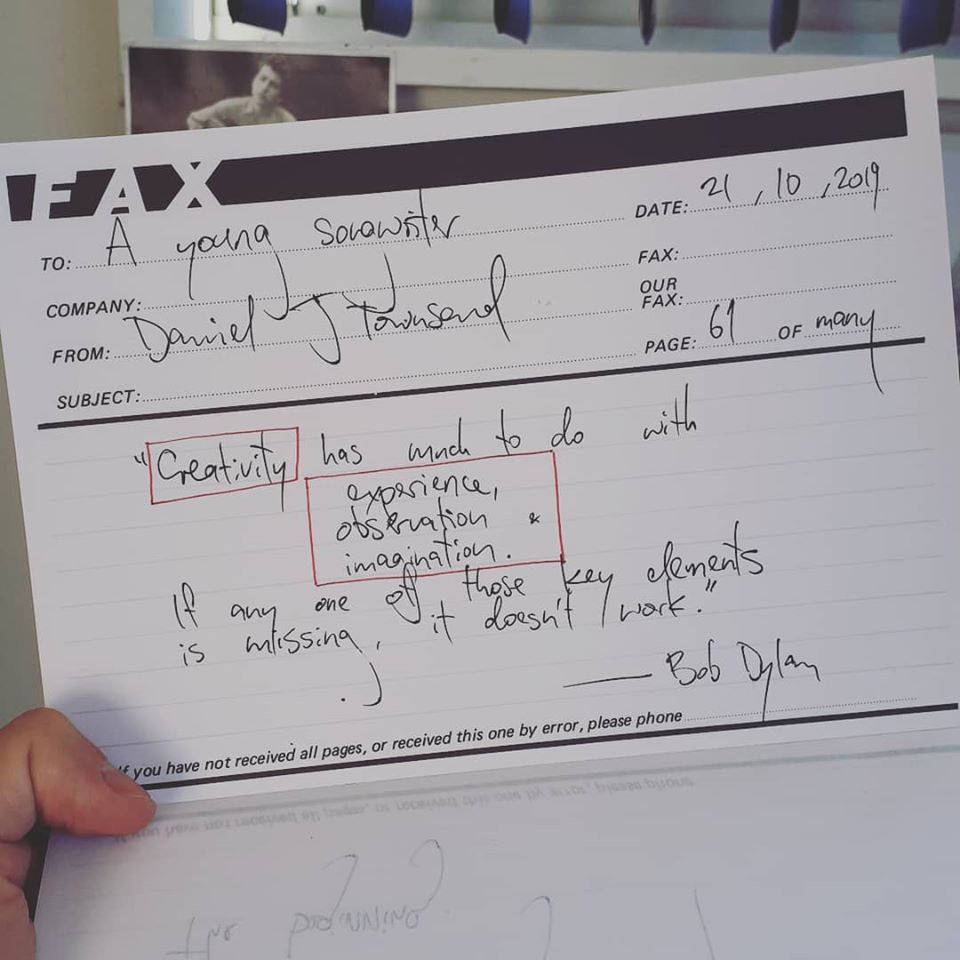

It can be hard to imagine that he had not considered writing songs. But we know the rest of the story. Back then he was only interested in experience and observation.

The imaginings would come.

He had learned hundreds of songs from a bunch of sources. Rare records, late night radio, that singer in the music store. Each song had a story or three, most had multiple versions from multiple performers, some had more than a dozen verses. Thousands of words. Memorised the lot of them and knew them deeply. Like I said, a folk singer.

It can be hard to imagine that he had not considered writing songs. But we know the rest of the story. Back then he was only interested in experience and observation.

The imaginings would come.

Have you read Stopping All Stations? It's a poem by Matthew Lambert, Barry Francis, Daniel Smith and Robbie Robertson. You probably know them as Hilltop Hoods.

If it's true that "creativity has much to do with experience, observation and imagination" (Bob Dylan), then Stopping All Stations is creative perfection. The poets tell three versions of one story. We see the event through the eyes of an elderly man, a young woman and a young man whose lives collide on an Adelaide train.

The genius of the piece is that we are compelled to empathise with each person in the story. Not only that, the writers start the piece with the character with whom they know their audience is least likely to identify: The polite old man.

Hilltop Hoods have never been the old man on a train, but they have been the rowdy young men. Experience. They've almost certainly hung out with the young woman in the story. Observation. And they have lived attentively enough to be able to fill in the gaps in the story. Imagination.

Stopping All Stations is perfect. Read it.

If it's true that "creativity has much to do with experience, observation and imagination" (Bob Dylan), then Stopping All Stations is creative perfection. The poets tell three versions of one story. We see the event through the eyes of an elderly man, a young woman and a young man whose lives collide on an Adelaide train.

The genius of the piece is that we are compelled to empathise with each person in the story. Not only that, the writers start the piece with the character with whom they know their audience is least likely to identify: The polite old man.

Hilltop Hoods have never been the old man on a train, but they have been the rowdy young men. Experience. They've almost certainly hung out with the young woman in the story. Observation. And they have lived attentively enough to be able to fill in the gaps in the story. Imagination.

Stopping All Stations is perfect. Read it.

If you ever want to develop your patience, take a toddler for a walk around the block. Make sure you all their parents first, otherwise it can get all kidnappy (with a kid in a nappy).

They will stop and marvel at individual bits of gravel while walking on a gravel path. They will point the stone out, make sure you've seen it, pick it up and sing to it or cuddle it. They'll give it a name like Daddy Gravel and they'll make it interact with the other pieces of gravel and the flowers in a way that inadvertently takes the piss out of the way you talk. Take a step. Do it again.

You can fight it or you can admit defeat and just roll with it. You get a certain look of resignation in your eyes which other Toddler Walkers will recognise: This is my life. I'm walking slowly to nowhere in particular, talking to gravel, filling my pockets with pebbles and petals and I don't even care any more.

Some toddlers see a world in a grain of sand. Heaven in a flower. An hour feels like an eternity while you're holding that little one's hand.

And it's good. At least, it's supposed to be.

At some point they learn that pebbles, petals and dawdling are the dumbest fuckin' things and that dawdling pebble-pickers are useless or insane or both. Or they don't. Amen to those little souls.

They will stop and marvel at individual bits of gravel while walking on a gravel path. They will point the stone out, make sure you've seen it, pick it up and sing to it or cuddle it. They'll give it a name like Daddy Gravel and they'll make it interact with the other pieces of gravel and the flowers in a way that inadvertently takes the piss out of the way you talk. Take a step. Do it again.

You can fight it or you can admit defeat and just roll with it. You get a certain look of resignation in your eyes which other Toddler Walkers will recognise: This is my life. I'm walking slowly to nowhere in particular, talking to gravel, filling my pockets with pebbles and petals and I don't even care any more.

Some toddlers see a world in a grain of sand. Heaven in a flower. An hour feels like an eternity while you're holding that little one's hand.

And it's good. At least, it's supposed to be.

At some point they learn that pebbles, petals and dawdling are the dumbest fuckin' things and that dawdling pebble-pickers are useless or insane or both. Or they don't. Amen to those little souls.

I love silence.

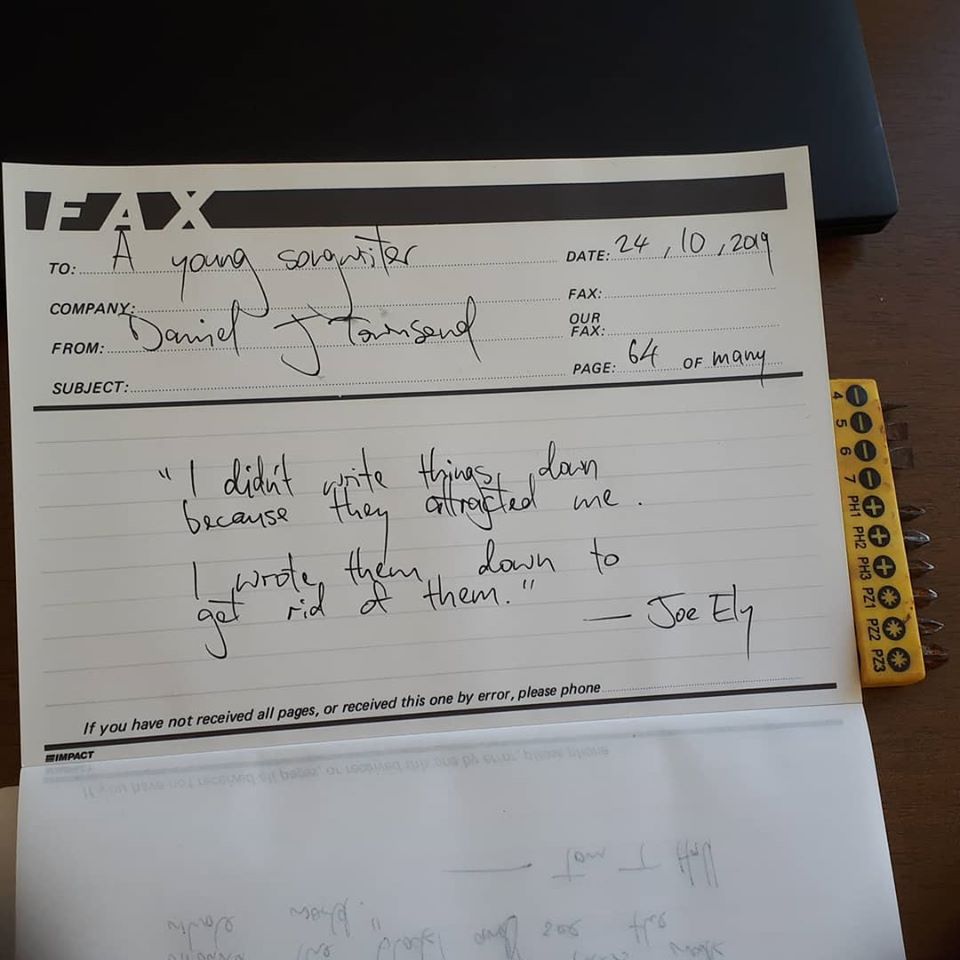

I once released an album I hated. During a promotional interview, the journalist said "It must feel good to get this one out." I said that it was basically a funeral for a few songs.

I loved that silence. Poor thing.

But it did feel good to release it. I don't think you necessarily only have to put out art you're proud of. You can put it out like rubbish on a Wednesday, just because you don't want the stink near your house any more. Release it like a splinter from your pointer, so you can get back to playing chords again. Launch it like a satellite so you can see yourself from a different point of view. Or just drop it.

Sometimes, on the other side of that ugly song, there is a beautiful song waiting to be written.

Or just a beautiful silence.

I once released an album I hated. During a promotional interview, the journalist said "It must feel good to get this one out." I said that it was basically a funeral for a few songs.

I loved that silence. Poor thing.

But it did feel good to release it. I don't think you necessarily only have to put out art you're proud of. You can put it out like rubbish on a Wednesday, just because you don't want the stink near your house any more. Release it like a splinter from your pointer, so you can get back to playing chords again. Launch it like a satellite so you can see yourself from a different point of view. Or just drop it.

Sometimes, on the other side of that ugly song, there is a beautiful song waiting to be written.

Or just a beautiful silence.

I released an album, even though I hated it. Here's what I did next:

I toured the album with the band to very underwhelmed audiences in mostly empty rooms. I hid my guitar under my bed and read heaps of short stories, heaps of books about religion and culture, and books filled with folk songs. I discovered The Artist's Way by Julia Cameron and saw the light. I went to art school and drew heaps. I wrote and self-published a book. I penned a lot of short stories and poems and put them on a blog. I chatted with my doctor and we decided I should come off the pills little bit by little bit. I went into therapy, put some important personal boundaries on place, left the band and serendipitously ran into an old friend (in the local library, where I had been borrowing all those books) and found out he had been getting into folk music. He'd bought a banjo. I had a bunch of orphaned songs from my band days. I visited his house with my guitar, recently retrieved from under my bed, and my songs found a family. We rehearsed a lot, then played gigs, and the songs found their audience.

My songs found a family. Then they found their audience. And here you are.

I toured the album with the band to very underwhelmed audiences in mostly empty rooms. I hid my guitar under my bed and read heaps of short stories, heaps of books about religion and culture, and books filled with folk songs. I discovered The Artist's Way by Julia Cameron and saw the light. I went to art school and drew heaps. I wrote and self-published a book. I penned a lot of short stories and poems and put them on a blog. I chatted with my doctor and we decided I should come off the pills little bit by little bit. I went into therapy, put some important personal boundaries on place, left the band and serendipitously ran into an old friend (in the local library, where I had been borrowing all those books) and found out he had been getting into folk music. He'd bought a banjo. I had a bunch of orphaned songs from my band days. I visited his house with my guitar, recently retrieved from under my bed, and my songs found a family. We rehearsed a lot, then played gigs, and the songs found their audience.

My songs found a family. Then they found their audience. And here you are.

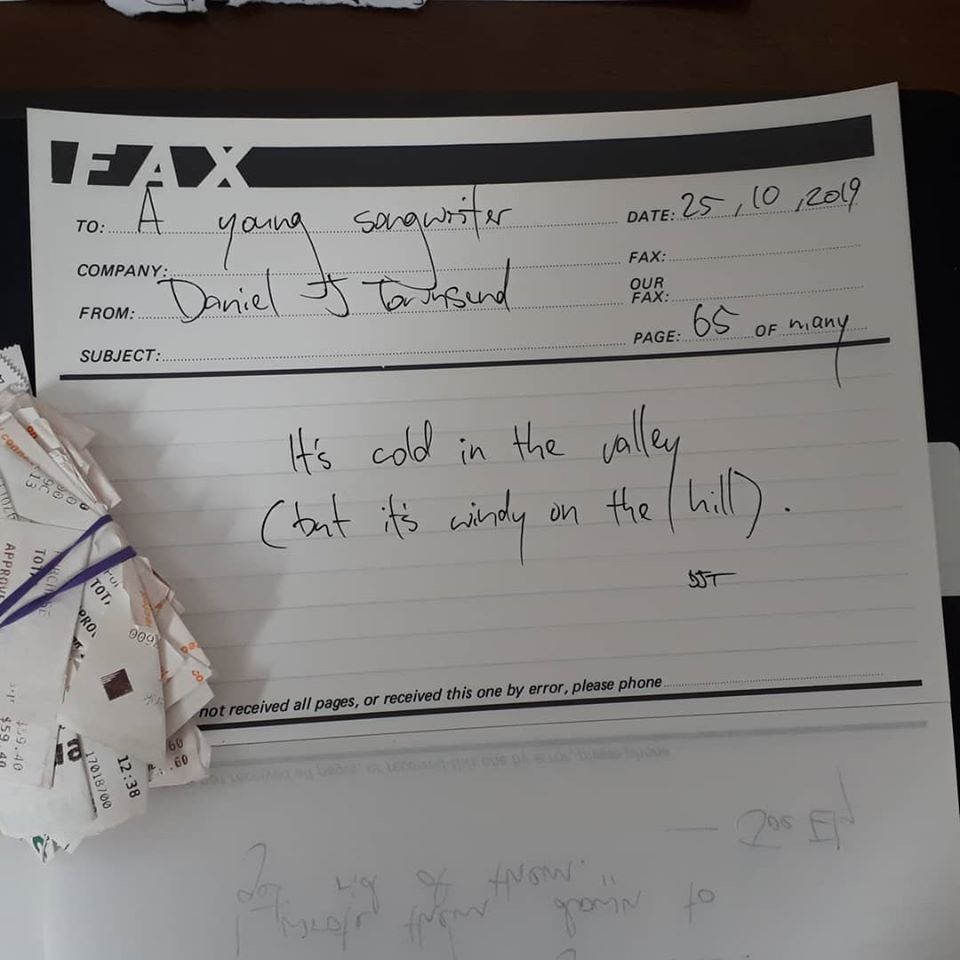

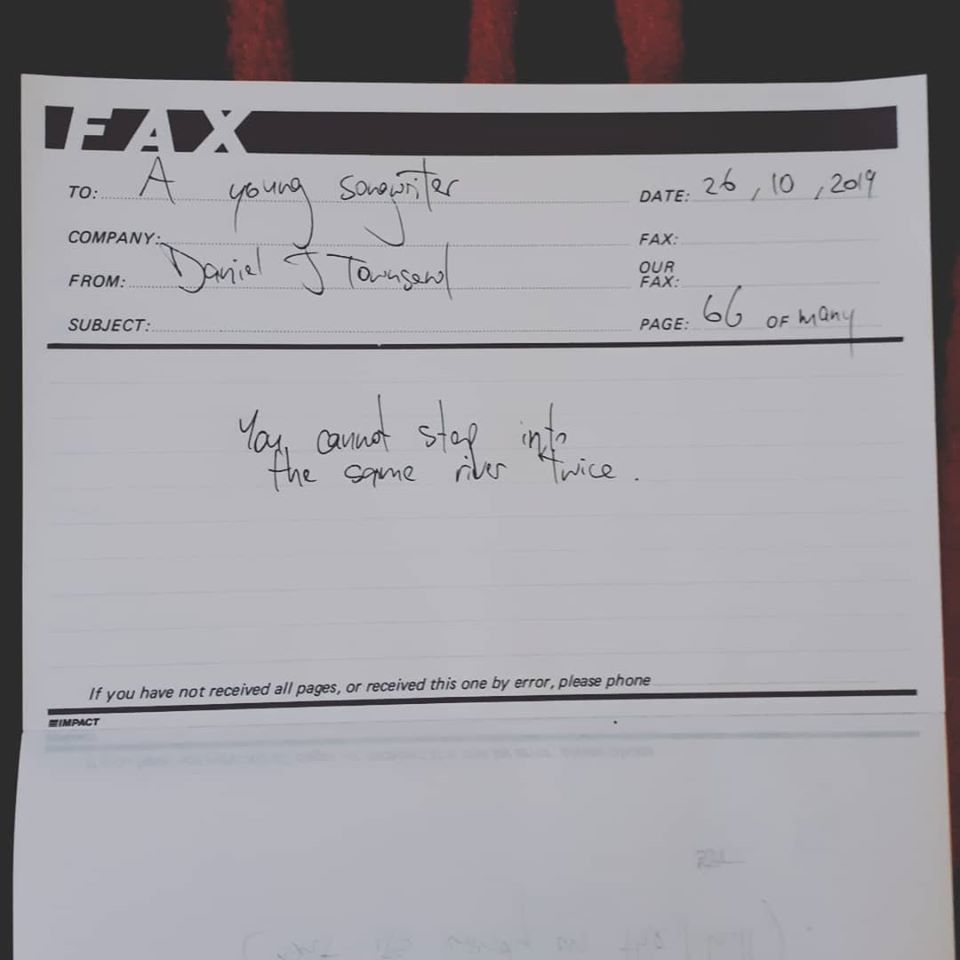

Last night I played a show accompanied by a guitarist friend. Somehow, all the songs felt new. We found our way into the night, arms and fingers stretching forwards. I'd never done it quite like that before.

This afternoon I host a songwriting workshop. I've written hundreds of songs, but I've never done it here, now, with whomever turns up. It's the first time I've done this.

Tomorrow I perform a new show, which I'm calling Broken Voices. I know what it's about, but it isn't fully formed. I'll think on it as I get around, maybe write a few things down. I don't know what it will look like, but I believe in it.

Into the river again.

This afternoon I host a songwriting workshop. I've written hundreds of songs, but I've never done it here, now, with whomever turns up. It's the first time I've done this.

Tomorrow I perform a new show, which I'm calling Broken Voices. I know what it's about, but it isn't fully formed. I'll think on it as I get around, maybe write a few things down. I don't know what it will look like, but I believe in it.

Into the river again.

I'm told French educators have a saying: "What teachers teach is themselves." Teachers tend to end up with classrooms that reflect their own strengths and weaknesses. Thirty 'Mini Me's.

Beware the teacher who criticises their class for being disorganised or uninspired.

I once taught a music class where the students were killing it in prac, but not a single student handed in the major written assignment we'd been discussing every lesson for a whole term. That sorta thing makes you stroke your chin, I can tell you. I'd taught them not to do the written assignment, to just avoid it. I had communicated that I didn't really want to see their work, and they had heard it clearly.

In a similar vein, what songwriters communicate is themselves. What you perform is yourself. And, when you find your audience, you'll discover that they are a reflection of you. Your vibe attracts your tribe.

The folks who talk to me after my shows are usually quietly spoken and perceptive. They are listeners and thinkers. Often they have cried during the show and tell me so. They repeat my lyrics back to me or ask questions about one of the songs. They buy a CD or a book and smile as I sign it for them. Sometimes they film me, but they rarely tag me or talk about me on social media. They don't make a lot of noise about me. Ours was a quiet, shared moment. In short, my listeners are like me.

What you perform is yourself. Get ready to meet yourself, again and again.

Beware the teacher who criticises their class for being disorganised or uninspired.

I once taught a music class where the students were killing it in prac, but not a single student handed in the major written assignment we'd been discussing every lesson for a whole term. That sorta thing makes you stroke your chin, I can tell you. I'd taught them not to do the written assignment, to just avoid it. I had communicated that I didn't really want to see their work, and they had heard it clearly.

In a similar vein, what songwriters communicate is themselves. What you perform is yourself. And, when you find your audience, you'll discover that they are a reflection of you. Your vibe attracts your tribe.

The folks who talk to me after my shows are usually quietly spoken and perceptive. They are listeners and thinkers. Often they have cried during the show and tell me so. They repeat my lyrics back to me or ask questions about one of the songs. They buy a CD or a book and smile as I sign it for them. Sometimes they film me, but they rarely tag me or talk about me on social media. They don't make a lot of noise about me. Ours was a quiet, shared moment. In short, my listeners are like me.

What you perform is yourself. Get ready to meet yourself, again and again.

There really is nothing like the experience of having a stranger come up to you after your show, as you are winding your leads, and they say they would like to buy your music. They want a little bit of what you have created, in their home. (What a vulnerable moment! Please sir, I want some more!) You offer to sign it for them. Their eyes light up. Your ask their name. They smile gently and answer. You check the spelling and they tilt their head to watch you write. You thank them for listening. They clutch the music to their chest. You wish them all the best. They look you in the eye, speak tenderly, and turn away.

Fish and bread, multiplied.

Fish and bread, multiplied.

Megan Washington has a song where she says her "dreams are too big for this space". I've seen her sing it in a tiny Launceston bar and I've seen her sing it in an enormous, sold-out Sydney theatre. The lyric rang true in both spaces. Her music calls her out. There is more. There is always more.

I've sometimes been told I'm wasted on the towns and venues that have me. Some well-intentioned punter will come up after the show, shake my hand and tell me I deserve better. That I should be somewhere else, singing for lots of someone elses. It used to make me feel alienated, but they're right, in a way. I'm good at what I do. As one friend said, I have a head full of stories, a soul old enough to have lived them, and a heart young enough to believe in their power to move us. This same friend also said what he likes about me is that I give a shit.

So, I care too much to settle. No amount of tiny Launceston gigs or sold-out Sydney theatres would fill me up, either.

I've sometimes been told I'm wasted on the towns and venues that have me. Some well-intentioned punter will come up after the show, shake my hand and tell me I deserve better. That I should be somewhere else, singing for lots of someone elses. It used to make me feel alienated, but they're right, in a way. I'm good at what I do. As one friend said, I have a head full of stories, a soul old enough to have lived them, and a heart young enough to believe in their power to move us. This same friend also said what he likes about me is that I give a shit.

So, I care too much to settle. No amount of tiny Launceston gigs or sold-out Sydney theatres would fill me up, either.

I have a friend who keeps every song she has ever written. Chronologically arranged in matching folders, it's like a time machine. You can go right back to the start, just like that.

I couldn't do it. I've tried to herd my song-cats, but so often they just want to sleep on the page they started on, or they run out the front door and onto the road. Sometimes they press, needy into my ankles and knees, silently demanding food I cannot provide. I write them a tasty line or two but they won't even look at me. Sometimes I revisit the lines months later. Often by that point the cat is blessed, blessed roadkill.

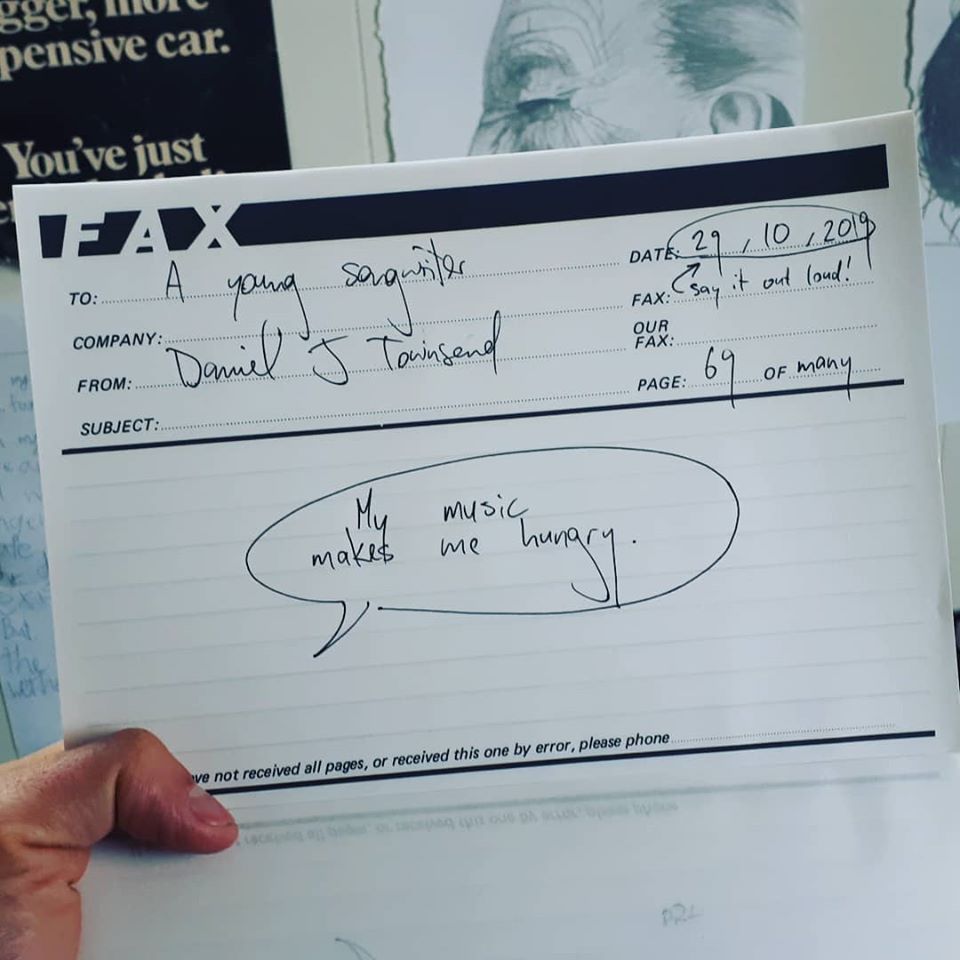

Most of my songs emerge from silence and return shortly thereafter. Some of my songs are medicine I've mixed for myself. (Another friend assures me, "If you like it, someone else is bound to like it too." He's probably right.)

And some of my songs spend nine lives dodging the cars out front, leaping from the front bar stage, getting tangled and strangled by cords in the studio. By the time you hear them, that cat is eternal. Or at least undead. Zombie cat.

I guess what I'm saying is, you have to kill cats to write good songs.

I couldn't do it. I've tried to herd my song-cats, but so often they just want to sleep on the page they started on, or they run out the front door and onto the road. Sometimes they press, needy into my ankles and knees, silently demanding food I cannot provide. I write them a tasty line or two but they won't even look at me. Sometimes I revisit the lines months later. Often by that point the cat is blessed, blessed roadkill.

Most of my songs emerge from silence and return shortly thereafter. Some of my songs are medicine I've mixed for myself. (Another friend assures me, "If you like it, someone else is bound to like it too." He's probably right.)

And some of my songs spend nine lives dodging the cars out front, leaping from the front bar stage, getting tangled and strangled by cords in the studio. By the time you hear them, that cat is eternal. Or at least undead. Zombie cat.

I guess what I'm saying is, you have to kill cats to write good songs.