|

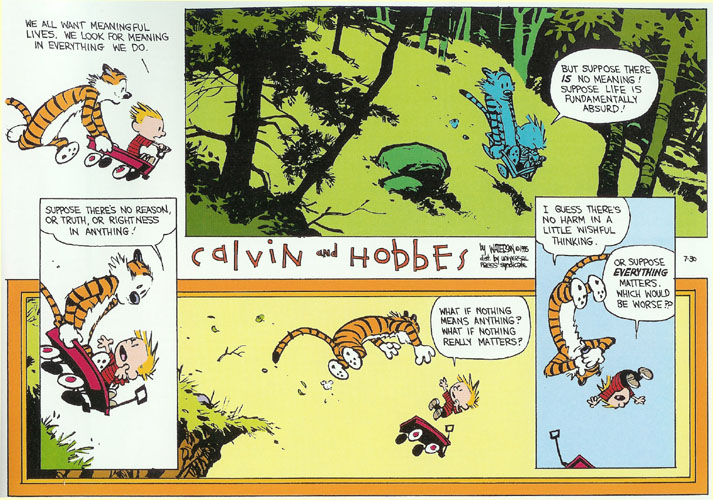

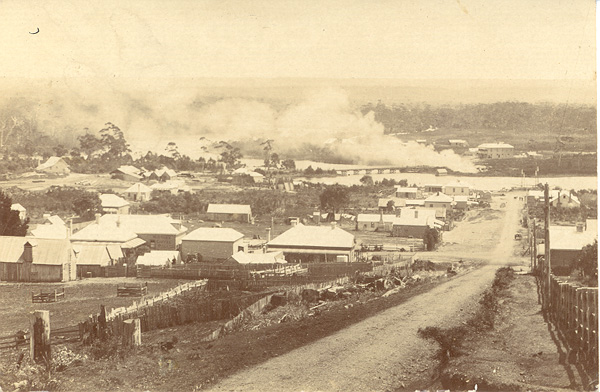

But so were you, right? Adolescence is all about extremes. The interesting thing is how you feel about it all afterwards. Some of us are proud of our extreme adolescence. Mostly we feel a little embarrassed. (Gosh. I was so idealistic. And that hair!) When we become grown-ups we tone everything down. Dulux has hundreds of shades of white from which you can choose to paint your home. (Just so you know, Hog Bristle is very 2009.) When you were a teenager, you dyed your hair pink - Hog Nose Pink - and felt angry a lot of the time. Now, you tone down your rage to a warm Dulux Natural White anger, but you only use it on your internal walls. When I was a teenage extremist I learned that my anger is a gift, I discovered "the power of the question" and I lived as if we need to take the power back. Thanks to these guys. My hair is its natural colour now. That's all. Musselroe Bay is a gorgeous little holiday town up on the north-east shoulder of Tasmania. At dusk, hundreds of roos and wallabies emerge from their mysterious daytime seclusion to graze, just like they have always done. The wind roars like a forty, just like he has always done, although the wind farm is new. When I visited for the first time in 2012, the Information Board down near the beach contained a story both unique and ubiquitous to 19th century Van Diemonian coasts. It was all sealers, fires on the coast, tea and flour, kidnapping... There must be a hundred places here with that story. The story was unique in the use of active language. History, especially the gruesome stuff, reads better in the passive voice ("Lives were lost...") rather than a voice which suggests people actually did stuff ("The sealers killed them..."). But the story was really unusual in that the writer had actually given a voice to the Aboriginal people involved. They were polite. Then they were concerned. Then they were horrified. And then they fought back. Musselroe Bay is a gorgeous little holiday town up on the north-east shoulder of Tasmania. The clock's little hand is edging towards the late night ten. My writer friend and I have been chatting for hours already and we're only warming up.

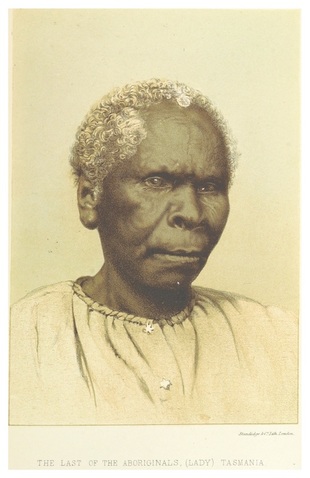

He tells me how a new idea can distract him from The World Out There for days at a time and how he'd stared at the ceiling for three hours the night before with a new paragraph lodged in his mind. I can relate. Just this morning I'd woken with new lyrics behind my teeth. As we are talking she appears in the hallway, wide-eyed with fairy pyjamas, bed hair braids and that perpetually loose front tooth. She's not supposed to be up after bedtime stories. When she speaks, it is with both caution and a kind of pride. "I couldn't sleep," she whispers. "Because I had a poem in my head." The page is in her hand, the carefully linked words written in green marker. Age Doesn’t Matter When my Mum's gone she'll be burnt and taken far to the wildest place. When my Dad's gone he'll be put in grave and go up to heaven I'm sure. Neither of them will live longer than me if we're always safe. Why does death have to exist? But age doesn't matter it's the person you are whether rich or poor. Cuddled up on my lap, with her page of poetry in my hand, my daughter is restless but relieved. Her little hands are still fidgeting as the clock's passes the ten.  A sailor stabbed her mother. A soldier shot her uncle. Sealers stole her sisters. Wood cutters cut off her fiancee's hands, killed him, then repeatedly raped her. Sailors, soldiers, sealers and wood cutters. These men had names, and addresses. They probably have living descendants. Aussies like victims. We like to think of her as a woman who life just happened to. Shit happens and she had heaps of it, right? Nup. When she was twenty nine, she joined with four friends to wage a guerrilla war against the invaders. They robbed huts, shot settlers and ended up killing two sailors. They were stockpiling weapons. She didn't wear a metal letterbox helmet, but she took em on. She was not a moderate. She was extreme. She was a bushranger, a rebel, an armed revolutionary. How could she have been anything else? When she disappeared, she wanted to be buried behind Mount Wellington. One hundred years later, her bones were returned from England. Her body was cremated and scattered on the same stretch of water on which she saw her fiancee killed. Her dust is in the sand. And that sand is still in my shoes. I think about disappearing at least once a day.

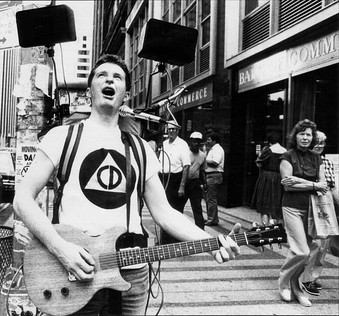

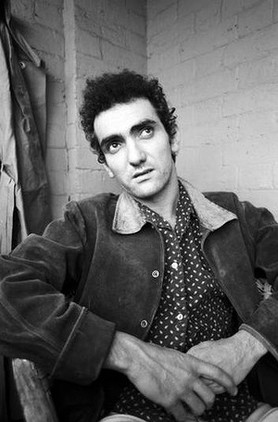

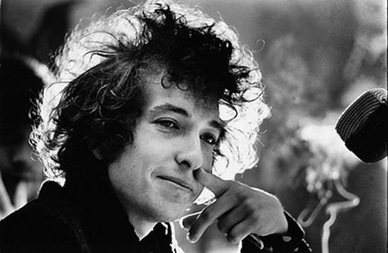

Which is not to say I am daily considering doing myself in. Not at all. I just think about how amazing it is that we all disappear. I will disappear. Maybe today, maybe in fifty years. There was a moment for me many years back, just like there probably was for you, when disappearing became a Thing: I had a friend, then I got a phone call, and it became apparent that I didn't have friend any more. Just like that. I know it's not news. It's been happening everywhere forever, but that doesn't make it any less magical to me. In the same way as parents-to-be speak about childbirth as if it's never been done, I speak about disappearing as if it is a brand new trick. But just because I know seven billion babies have been born this century doesn't mean I know how to hold my own newborn for the first time, and just because I know we all disappear doesn't mean I have any idea how to do it. I just find it so hard to believe. I'm here. One day I won't be. I wonder how differently I would live if I really believed in my impending disappearance. Seems to me people either go nuts or go Gandhi with this kind of knowledge. Or they just distract themselves in one of a million ways. Today I chose distraction. But I'm one day closer regardless.  I heard a woman say it on the radio today. We all disappear, she said. She was referring to death and dying. You're here, then you're not. The people closest to you will cry, hang your picture, remember you until they can't and then you're gone. But sometimes people reappear, long after they've achieved their silent, nameless transparency. Take my earliest Van Diemonian ancestors. Buried in unmarked graves by their embarrassed children, John and Agnes disappeared quicker than most. She was born in Glasgow, Scotland in March 1832. She had a mum, a dad, a brother and a sister. When she was 16 she was caught stealing clothes and sent by boat, an unaccompanied minor, to the other end of the earth. Do you remember what you were like at 16? The records tell us she was ruddy and freckled with brown hair and light blue eyes. Can you picture her? She could read and write too. When they banished her from Hobart Town she was a tattooed state-made orphan. He was 30 when they wed in Launceston on April 21, 1851. The couple moved to the north west coast of Tassie and lived on a farm with their kids. In time, they were hidden in the earth. Yesterday, my uncle sent me an email. I clicked on the attachment and John Townsend appeared. We all disappear. Sometimes, we reappear.  My favourite songwriters sing badly. There are two sides to that coin. Their barking gives the impression that they have lowered the bar for the rest of us, when in reality they have raised it. Because, like, if they can make an impact sounding like that then, like, you should totally go on X Factor. I took great courage from his music. He wrote some songs which could have been penned at any point in history and he wrote some songs which could have come straight from his diary. He sang about love and death, sex and life, politics and religion. All the stuff his people, the English, didn't talk about, and yet somehow he was so very English. I admired his honesty. I envied his passion. I even sought out certain books because of the histories I had heard in his lyrics. He helped me to feel, made me think and helped me to make some very important life choices. I loved his voice. And I knew he had the market cornered on locally accented singing. So I just walked straight under that sky-high bar, with a low guitar and a voice entirely mine. Between The Wars (1985) I was a miner I was a docker I was a railway man between the wars I raised a family in times of austerity With sweat at the foundry Between the wars I paid the union and as times got harder I looked to the government to help the working man And they brought prosperity down at the armoury "We're arming for peace me boys" Between the wars I kept the faith And I kept voting Not for the iron fist but for the helping hand For theirs is a land with a wall around it And mine is a faith in my fellow man Theirs is a land of hope and glory Mine is the green field and the factory floor Theirs are the skies all dark with bombers And mine is the peace we knew Between the wars Call up the craftsmen Bring me the draughtsmen Build me a path from cradle to grave And I'll give my consent to any government That does not deny a man a living wage Go find the young men Never to fight again Bring up the banners from the days gone by Sweet moderation, heart of this nation Desert us not We are between the wars  A good songwriter gets your attention. A great songwriter diverts your attention to other great songwriters. A brilliant songwriter can change the way you see everything. Every Australian song I'd ever heard sounded like sunburn, truck tyres, red dust and the wide open blah blah blah. Places I'd never been, but places I'd been tricked into believing were my home. When I discovered this guy, my country sounded like the bend on Kensington Road, like whiskey and fishing, like the Colonel Light statue, like the backseat at seventeen, like a crowded beach with the big kids out past the breakers. This gentleman made me aware that the big red country myth had left me feeling homeless. I have always lived in the suburbs, like almost everyone in this country. I got married early, never had no money and am thankful she didn't take the kids when I went crazy. Love like a bird flies away, so I'm told. These days many of his songs are about getting old, about loving the fine lines time has drawn on her face, about the spring and fall of a life of love, but I just can't yet relate. I've only lived to the fifth verse. Deeper Water (1995) On a crowded beach in a distant time At the height of summer see a boy of five At the water's edge so nimble and free Jumping over the ripples looking way out to sea Now a man comes up from amongst the throng Takes the young boy's hand and his hand is strong And the child feels safe, yeah the child feels brave As he's carried in those arms up and over the waves Deeper water, deeper water, deeper water, calling him on Let's move forward now and the child's seventeen With a girl in the back seat tugging at his jeans And she knows what she wants, she guides with her hand As a voice cries inside him - I'm a man, I'm a man! Deeper water, deeper water, deeper water, calling him on Now the man meets a woman unlike all the rest He doesn't know it yet but he's out of his depth And he thinks he can run, it's a matter of pride But he keeps coming back like a cork on the tide Well the years hurry by and the woman loves the man Then one night in the dark she grabs hold of his hand Says 'There, can you feel it kicking inside!' And the man gets a shiver right up and down his spine Deeper water, deeper water, deeper water, calling him on So the clock moves around and the child is a joy But Death doesn't care just who it destroys Now the woman gets sick, thins down to the bone She says 'Where I'm going next, I'm going alone' Deeper water, deeper water On a distant beach lonely and wild At a later time see a man and a child And the man takes the child up into his arms Takes her over the breakers To where the water is calm Deeper water, deeper water, Deeper water, calling them on  Authentic songwriters and musicians somehow seem to "beget" songwriters and musicians in their likeness. Most modern songwriters can trace their lineage back to this guy, directly or otherwise. I call him my grandfather-in-song and he is, these days, quite grandfatherly and very much an elder whether he likes it or not. He probably doesn't. He doesn't seem to like much. His music touches me deeply. He's easy enough to imitate and denigrate, and if you don't get him you probably won't get him, but if you do then there's not much I need to say. Even now, his music is "the sound of a young man in a hurry". He speaks for himself, so he speaks for me. Because he did and does his thing, I can do mine. Try reading these words aloud. Go on. You're probably in there somewhere. "Condemned to drift or else be kept from drifting". That's me. Chimes of Freedom (1963) Far between sundown’s finish an’ midnight’s broken toll We ducked inside the doorway, thunder crashing As majestic bells of bolts struck shadows in the sounds Seeming to be the chimes of freedom flashing Flashing for the warriors whose strength is not to fight Flashing for the refugees on the unarmed road of flight An’ for each an’ ev’ry underdog soldier in the night An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing In the city’s melted furnace, unexpectedly we watched With faces hidden while the walls were tightening As the echo of the wedding bells before the blowin’ rain Dissolved into the bells of the lightning Tolling for the rebel, tolling for the rake Tolling for the luckless, the abandoned an’ forsaked Tolling for the outcast, burnin’ constantly at stake An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Through the mad mystic hammering of the wild ripping hail The sky cracked its poems in naked wonder That the clinging of the church bells blew far into the breeze Leaving only bells of lightning and its thunder Striking for the gentle, striking for the kind Striking for the guardians and protectors of the mind An’ the unpawned painter behind beyond his rightful time An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Through the wild cathedral evening the rain unraveled tales For the disrobed faceless forms of no position Tolling for the tongues with no place to bring their thoughts All down in taken-for-granted situations Tolling for the deaf an’ blind, tolling for the mute Tolling for the mistreated, mateless mother, the mistitled prostitute For the misdemeanor outlaw, chased an’ cheated by pursuit An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Even though a cloud’s white curtain in a far-off corner flashed An’ the hypnotic splattered mist was slowly lifting Electric light still struck like arrows, fired but for the ones Condemned to drift or else be kept from drifting Tolling for the searching ones, on their speechless, seeking trail For the lonesome-hearted lovers with too personal a tale An’ for each unharmful, gentle soul misplaced inside a jail An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing Starry-eyed an’ laughing as I recall when we were caught Trapped by no track of hours for they hanged suspended As we listened one last time an’ we watched with one last look Spellbound an’ swallowed ’til the tolling ended Tolling for the aching ones whose wounds cannot be nursed For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones an’ worse An’ for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe An’ we gazed upon the chimes of freedom flashing An elder is a leader or a senior figure in a tribe or other group.

Every society everywhere at any point in the past squillion years has had elders; respectable and respected older folk who keep their people on the well-beaten track. Societies with unheeded elders either end up killing themselves off or getting taken over. Elders have been a normal part of the world until very recently. For the most part, these days us Westerners put them in homes or - worse still - we don't even know who they are. The twentieth century saw more humans killed by humans than all the previous centuries combined. So it's probably not that surprising that, about half-way through that century, we began killing off our elders in an attempt to fix things. The Beatles knocked off one variety of elder when they became more popular than Christ (and therefore more relevant than his earthly representatives) in 1966 and in 1968, a 28 year-old John Lennon helped antiquate the notion of elders when he declared that we ought not trust anybody over 30. Pretty soon young people were each disappearing into their hyper-individualist minds. We're pretty much still there as a society. It's all about me being and staying young and sexy and happy. Forever young. While we were chasing the white rabbit, grown-ups reemerged from behind their charred forts and went into advertising. They learned how to make us fear becoming old (old people created the holocaust, Sunday School and grey trousers) and how to get us to switch our ears off to people who actually know how life works, based on experience and reflection. I think we're afraid of dying and old people make us think of death. Simple. We forget that an elder is "a leader or a senior figure". You don't have to be old to be an elder, but you do have to be a leader. So, for the next few posts, I'm a-gonna write about my favourite elders. Leaders, the lot of 'em. A wonderful family member gave me a book for my birthday. It wasn't my birthday. I tried telling her but thankfully the book arrived in the mail anyway. It's the story of a chimp adopted by a childless couple. The narrative bounces from focusing on humans to ape and back again, chapter to chapter, until it's hard to tell who is who.

I'm an ape. I know, because I don't think I am one. If a chimpanzee does not need another to acquire food, he will not bother trying to get along with anyone. And if he wants the help of someone, he will always choose the one he has found success with in the past. As a little monkey with a drum I am in the thick winter of what I call Festival Rejection Letter Season. As you may know, these letters are group emails from the festival organisers explaining how they received too many applications, how the standard was high and how artists have been selected based on a combination of merit, their fee and what they may be able to contribute to the festival. So, I get the Thanks But No Thanks unless, of course, I know someone at the festival or have played it before. Wherever they are, apes invent culture and their culture is strengthened through the exclusion of others. Ever been there? Geez... There are leopards in the memory of every ape, leopards never seen. Some look like dragons and some look like drains. Maybe I'm a leopard. It is an ape instinct to look down on other apes. I feel like throwing poop at a bunch of monkeys today. Back when I drove with P plates I worked a few extra shifts at the pizza store to be able to afford to see my favourite band play in my home town. If I didn't do any deliveries, I got paid twenty bucks a night. I'm fairly certain the ticket cost thirty bucks, so the ticket was of similar value to a couple of my Monday evenings spent staring at the drinks fridge. So I did the time, bought the ticket, stood front row centre, made eye contact with the singer, had a life changing experience, blu-tacked the ticket stub to my wall and so forth. This band is set to visit my home town for the first time since that time, way back when the internet lived inside a squawky modem next to beige 486s, and tickets start at two hundred dollars. Two bloody hundred bloody dollars. It's such a boring, tired story that I'm annoyed with myself for becoming a character in the plot - that of the jilted ex-fan who prefers the band's older stuff. I used to be the guy who wore the t-shirt before K-Mart stocked their CDs in bulk, and after that I was the guy living a life shaped by that front row experience. But whether those tickets are thirty dollars or two hundred dollars, there are only a few spots right up the front. And you only need to be there once. Old Reg is a Modern Serf too, but with a difference: He has no delusions of upward mobility.

Reg does not want to be a Modern Freeman. He rents his house, even when he could have paid for the place three times over by now, because he likes having a landlord to fix the taps for him. He likes having a landlord. For Reg, the so-called rental trap has been a pretty cosy place to live for half a century. He is a Modern Serf with a difference because he does not strive for more and, unusually for most Modern Serfs, the grass is actually greener on his side of the fence. Greener, less weedy and with perfect edges. Reg's lawn is where it's at. Just ask him. He doesn't want a bigger house with a bigger lawn. He doesn't even want to be the owner of his lawn. He wants for nothing. But sad songs in a sunny doorway really make him smile. Now, click Like and hurry along. Reg moved into the co-joined Commission house in 1964. He was 48. People said his wife had died. His kids were long gone and were not far off having their own littlies.

Reg planted his front garden with poppies, tulips and a hedge the year before the pound became the dollar. He watered his back lawn every morning, spraying flat weeds and thistles until his square yard was bowling green perfect. Chooks cluttered and laid in a special coop up the back of the garage. Finches tweeped in a tiny homemade aviary. Lawn clippings were scattered behind the treated pine garden edge where pumpkins, potatoes, carrots, beans, sprouts and lettuce slumbered beneath the soil. Decimal currency changed very little, the metric system even less. He would measure in inches, yards and miles til they put him six feet under; probably til the day Midford stopped making sky-blue long sleeved business shirts and wide-legged grey slacks. Come washing day the Hills Hoist was wooden pegged full of them. He'd hang his undies closest to the centre pole, as if even the clothesline deserved dignity. On warm days he'd sit in the doorway out front, screen door baling twined open, thinking of nothing. Or his wife. Or his kids. Or how different Tassie was nowadays, all short skirts and ridiculous music. Sunday mornings he'd listen to the country music station on the wireless. Sunny Sundays were sad songs in the sun. For some folks, life if simply one fine day repeated. The day the ambulance came, a truckload of men dug up his lawn so he could have faster internet. On that night I sat behind the Merch Desk and watched as your voice disappeared into the air They spoke. You sang. You stopped. They didn't. So you unplugged and walked to the middle of the room Flesh and blood, flannelette, timber and steel Real And we were yours For we are made not of cables and leads, we are able to bleed And those speaker stacks black the very sky we need for dreaming And you stood within the sound of silence And we heard it like a distant memory And we knew it like a dawning daydream And we felt it like a schoolyard crush, like an old man's tears and all the lonely, lonely people I cried my eyes out then as now. Twice around the sun and you can no longer find an empty room, Cannot step from today's stage into the emptiness, Loaf and fish in hand. You are flesh and blood in a flannelette shirt, timber and steel, Alone in a crowded, crowded field. I am a Modern Serf. I live on someone else’s land, work for someone else in exchange for food and safety, and will pass on my social status to my offspring.

I’m also a sixth generation Vandemonian. The first Tasmanian Townsend is buried in an unmarked grave with his scandalous tattooed wife, banished from Hobart Town to the north-west of the state. When older folks meet me today, they identify me as “from the north-west” even though my father left that coast nearly four decades ago. I have never lived in that part of this state but, like my dad and his dad, I am somehow a part of the land there and that land is a part of me. I am an artist, my old man is a pastor, his father was a builder and his father was an aspiring doctor forced to work on the family farm. Serfs, the lot of us, working on someone else’s land hoping one day it will be ours, and all the while the land of that north-west coast was somehow seeping in through the soles of our feet into our very being. We wanted to own those paddocks, but the soil ended up embedded in between the lines on our palms, billowing in our slow-moving speech and our gale force hearts. Of course we never really possess land, do we? The stuff slips through our fingers like what it will always be, the pursuit of dirt being one big distraction from what we’re actually alive for. One day, the land beneath our boots will possess us, transform us, turn us into something new. Maybe today.  A friend introduced me to the phrase “modern peasant” this week. I hadn’t thought of myself as a peasant before.

In the old days, there were three kinds of peasants: slaves, serfs and freemen. These days most of us are serfs (which sounds like Smurf, so I quite like the word) aspiring to be freemen (which sounds kinda gross). I am a Modern Serf. Back then, serfs lived on a plot of land and worked for the landowner in return for a few exorbitant luxuries such as protection, justice and the right to find food in designated paddocks. Modern Serfs still tend to live on plots of land owned by wealthy people, although often we choose to very slowly pay for that land so we can live on it and feel like it’s really ours. Modern Serfs still tend to work for landowners too, although instead of the landowner providing us with protection, justice and the right to forage they provide us with money so we can buy our own home security systems, health insurance and groceries. Back then, if you were born into peasantry you were stuck there and pretty bloody aware of your place. We Modern Serfs, of course, have a wide variety of career options and life choices to distract us from the fact. Back then, peasants were at the bottom of a three-runged ladder. The other rungs were the clergy and the nobility. I wonder who the Modern Clergy and Modern Nobility are. I am a Modern Serf. I like the way that sounds. To be a modern person is to be lonely, bored, anxious and passive.

That is, according to the German psychologist-philosopher Erich Fromm. This is the great mind who reinterpreted the story of Adam and Eve to be a virtuous one. He pointed out that being able to distinguish between good and evil is generally considered to be a good thing, but that biblical scholars usually speak about Adam and Eve in the same way that teachers speak about naughty children. Fromm praised Adam and Eve for actually having a go and not just doing what they were told. He reckoned this is what made them truly human: weighing up the situation and then taking action. And Fromm said that the most profound characteristics of modern people - of you and me - are loneliness, boredom, anxiety and passivity. That last one is the word that sticks with me. I'm such a sit-and-watch-the-wheels kinda cat. And anything beyond this point would amount to a sermon or a lecture from me, some pseudo-authority handing out fruit-eating guidelines. You work it out. I will too. Let's compare notes in a week. Or not. It's up to you. I have never met a terrorist. Or, at least, I don't think I have. It's been so long since I've had to be alert but not alarmed. Terrorism has changed the world and Australia is not immune, but the way of life which we value so highly must go on. We are friendly, decent, democratic people and we are going to stay that way. Our security agencies have been upgraded and are ready to detect, prevent and respond to terrorism. All of us can play a part by keeping an eye out for anything suspicious. Over the coming weeks the Commonwealth Government will be providing us with more information on how we can work together to protect our way of life. Be alert but not alarmed. Together, let's look after Australia. Voice or no voice, we can always be brought to the bidding of our leaders. It's easy. All they have to do is tell us we are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country... Oh, man. Be alert but not alarmed. Seriously. If the world in 2014 starts looking like the world in 2001-2003, be very bloody alert. And don't get distracted. Stay focused. Love or fear. Love or fear. Love or fear... Most stories are true. Some are factual. This story is both. It was the weirdest thing. There was somewhere I had to be. I'd tied my shoes to tired feet, took a left on David Street and drove beneath the brand new leaves up towards the evergreens. I'd had the most ghastly dream the night before, and it was hanging around, just out of my line of sight, like a young child about to interrupt a conversation. The memory of the moment weighed on my mind and pulled me under, just below the surface. I wasn't there. Tim Hart's debut, Milling The Wind, was on the car stereo. The volume was at thirty. I know, because it's one of my Things to have the volume set to a round number. Forty is good for listening to new lyrics or singing a third above. Fifty leaves your ears ringing. I've never gone above sixty. So, I turned up David Street with night visions still cluttering my mind, driving towards the bad news I didn't yet know was coming. And here's the weirdness. The music started to get louder. I don't mean the music on the recording got louder, I mean the stereo began to play louder. The CD player turned itself up. It was as if the hand of an invisible passenger was suddenly twisting the dial. The numbers on the face of the stereo whizzed through the background thirties, the singalong forties and the ear-ringing fifties, and stopped at 74 precisely. It was thunderous. And I heard Tim Hart singing, very loud and very clear: "Every man I know has the will to carry on / To carry on." I couldn't twist that volume quick enough. My dashboard had shuddered, my chest had hummed and I'd heard those words like they were shouted just for me. At me. "Every man I know has the will to carry on / To carry on." And I drove up David Street, towards the news I didn't yet know was coming. |

Archives

July 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed